booktube: a marketplace of discourse & the morality of media consumption

dissecting the subgenres of books, and thus bookish internet content

I wrote the following essay back in April/May for an English class called “Genres of Contemporary American Literature.” I’ve since made some edits; please excuse the slightly more academic or formal language.

I think it’s fair to say that the development of social media ecosystems entirely and exclusively dedicated to books has democratized who shapes the landscape of literature through the publishing market and online discourse.

Being a booktuber myself, no one checked that I had an English degree before I started creating and posting videos of me talking about books online. (I did not have an English degree.) Booktube provides a space for book recommendations and reviews offered by people with no proven authority on literature outside of their audiences’ legitimization of their tastes and opinions. In this way, our authority on books as exercised in the online landscape of book reviews and bookish content deeply shapes the publishing market. We are ‘influencers’ the way anyone with an intentional and monetized social media presence is.

Online influencers operate as figures of authority on how to live and what to consume in the contemporary world to audiences who are able to interact with and affect those figures—book influencers are no different. Obviously, we “influence” which books get bought and read. But more than that, as cultural commentators reviewing contemporary literature and discourse to a present, eager, and engaged audience, how we engage with and create the discourse that proliferates in online book spaces maps a moral world of consumption, media criticism, and self-stylized identities accessible through booktube.

In facilitating media consumption and criticism, booktube presents a marketplace of books that range between deserving of promotion or denigration, while also forming a ‘marketplace of ideas’ that often collapses opinions on books with personal morality and intellect. Whoever has the hottest take on the hottest book gets the most time at the mic with the biggest audience in front of them.

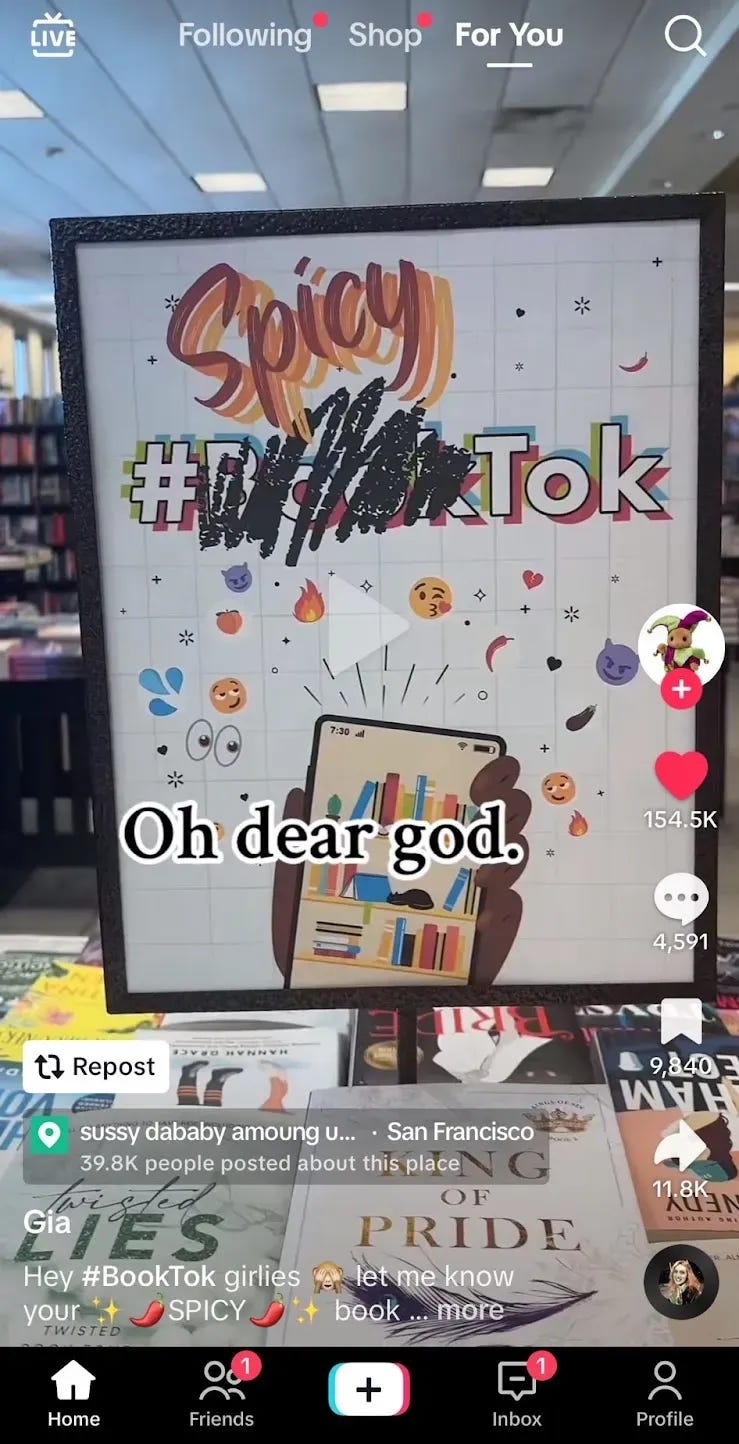

As reflected in the literal market of books and the publishing industry itself, bookish Internet spaces have gotten increasingly tied up with the process of selling books. Display tables and the layout of the largest in-person bookstore chain in the United States, Barnes and Noble, often feature books displayed by online popularity and even the bookish internet’s typification of given books. BookTok, which I think is an inevitable offshoot of booktube in the short-form video format that is friendlier to the minuscule attention spans the internet fosters, gets its own display table at Barnes & Noble's: “As Seen On #BookTok.” Or, as I saw on TikTok, a Barnes & Noble table display sign “#SpicyTok.”

As a form of marketing, consolidating all the “SpicyTok” books—so the erotic novels that booktok has popularized—into one area of the bookstore is effective in getting interested readers to purchase and read those novels. On the other hand, landing on the New York Times Bestseller list or getting a Pulitzer nomination, as examples of institutions of ‘legitimate’ institutions of literary authority and taste, has always and continues to provide significant clout for author, publisher, and reader.

But the specific, targeted, and personal nature of online book recommendations, discourse, and content in general offers a different sort of legitimacy and established authority between reader and recommender, one that constitutes a broader ecosystem of booktube. The viewer's opinion is either confronted, affirmed, or informed by the booktuber they are watching. Through the legitimacy of literary opinion that viewers provide booktubers by engaging with their videos, booktubers contribute to and foster cultural discourse regarding media consumption and identity.

Using the common language and approach to contemporary literature that booktube fosters, with all its typifications of books and identity and equivalencies made between media consumption and criticism with personal morality and intellect, booktube does not merely exist as a site of recommendations and reviews. While lots of booktube content does contain those things, what underpins much of how this social media ecosystem engages with literature is the self-stylized personalities, moral identities, and parasocial self-identification that comes with it.

Of course, booktube as a site for book recommendations requires engaging with a parasocial online dynamic. A viewer who takes a book recommendation from a booktuber they have already developed a parasocial relationship with will have higher expectations that the book will be one they enjoy, at least more so than if they took a book recommendation merely from institutions of literary esteem or market success. Book recommendations from almost any other source feel broader and more generic, because they are.

With the saturation of bookish content online produced by influencers with dedicated book-centric social media presences, the sheer breadth of booktube content allows for readers to readily access and consume content tailored to them. The diversity of content, as well as the fundamental role (besides being yet another form of online entertainment) that booktubers play as book reviewers and recommenders, expedites the exposure and introduction of books to viewers. Arguably, the personalized aspect of booktube works more effectively to get people to purchase and read books than bestseller lists, celebrity book club selections, and critical acclaim via literary award nominations.

Social media allows almost any and all books to be recommended to millions of people in a targeted and effective manner. On a smaller scale, if a viewer’s favorite books are also a booktuber’s favorite books, that booktuber’s recommendations of other books then feel personalized to the viewer. No other format of book recommendation list—beyond, of course, the probably rare experience of getting book recommendations in real life from your friends who personally know you and with whom you share similar literary taste—offers such a level of personalized book recommendation experience.

Specific identities of booktubers in the online book world provides a targeted marketing opportunity for the publishers marketing contemporary books. This exists within the larger context of social media marketing and an ever-elusive system of digital dissemination (often just referred to as “The Algorithm”), which helps present specific books directly to the readers who are ostensibly those books’ intended audience. It’s very effective. When someone I watch on booktube who I feel has very similar taste as me recommends a book, I am far more likely to buy and read that book than any other book I encounter in the wild. If I get a bookish Instagram posts in my feed on the Explore Page or “Suggested For You” posts on my home feed, they often feature books I’ve already read and enjoyed, or books I hope to read in the future. Or, they’ll be books I’ve never heard of and now am interested in reading because they landed on my feed.

A major appeal of watching booktube is the ability to access book recommendations from a person with an online presence the viewer can personally relate to. But I argue that the popularity of watching booktube over, for example, reading and following a book blog, where the individual book reviewer's personality is often still deeply involved, emerges from the consumer’s ability to access book recommendations directly associated with any given booktuber’s life, appearance, and personality as presented in their videos. Long-form—and even short-form—videos on social media platforms allow an intimate look into the lives of other readers, literally constructing what a “reader” can look like.

With the popularity of reading vlogs as a genre of content, viewers can get a close look at the curated aspects of the day-to-day lives and experiences of booktubers. The “relatability” aspect of booktube content also operates aspirationally; comments on booktube videos often contain some variation of “I wish I read more books like you do.” It seems to indicate that for audiences, reading is a morally good thing to do, and they want to do it more. They also want to read things that reflect who they are, care about, and aspire to be. We as viewers and social media users are attracted to the next best version of ourselves that we can find online, and if what I read is who I am and it defines me and my personhood, booktubers’ personalities and identities are that much more relevant to who we get our book recommendations from.

Jess of sunbeamsjess, a YouTuber who I’ve watched for probably a decade now, has in recent years shifted her content from fashion, beauty, and lifestyle to more bookish videos. She has also recently launched a Substack, end matters, where she writes in her second post titled “get to know me: reading edition / why knowing your reviewer's taste matters”: “Most of us who’ve dipped a toe into the worlds of bookstagram, booktok or booktube will know that we tend to gravitate towards those creators who read broadly the same genres as we do. But I would say getting the most out of your online browsing needs even more granular attention paid to taste, and the taste of your reviewer.” Beyond the taste of the reviewer and appeal as an influencer booktubers offer, the identity of said book reviewer and influencer becomes crucial to understanding why and how they like the books they do. Especially when contextualized within the vast array of bookish content creators in the marketplace of booktube, the “taste of your reviewer” fundamentally determines how and why you engage with their content.

Like other forms of the bookish internet, booktube content often depends on the interactive and derivative nature of this particular internet ecosystem. Looking at popular types of booktube videos from a sample of recently uploaded videos, many of the titles and concepts of these videos refer to and depend on the rest of the booktube landscape. When booktubers recommend “underrated books,” those books obviously exist relative to and in contrast with the books that are popularly discussed and recommended on booktube. When booktubers and their viewers use the term “DNF,” an acronym for “Did Not Finish,” it is rarely in the form of an actual acronym that you can spell out in the sentence with it still making sense. “DNF” becomes a verb rather than just an adjective describing a book that you did not finish; “books i dnf’d” as a video title from Mina Reads exemplifies the usage of this term in booktube terminology. The term “DNF” no longer functions as an actual acronym. Spelling out the letters of the acronym, “books I did not finish’d” doesn’t make sense. But you’ll likely find it difficult to see a booktube video titled “books I DNF,” even though spelled out, it just makes more sense to say “books I did not finish” rather “books I did not finished.” Same with the term “TBR,” or “to be read.” People often describe books as “being on my TBR” to refer to books that they want to read eventually. But same with “DNF,” most of the time the spelled out acronym does not make sense in that sentence. Then there’s the use of the term “unhaul,” which is the reverse of “hauling,” or purchasing items and showing them off, where you display the books that you are discarding for one way or the other. Booktube as an online ecosystem has its own language. It’s a language designed by and for book-centric social media users, and the literal applications of these terms often do not really make sense outside of this online context.

It’s crucial to note that there’s a whole genre of content on booktube that is just using other online book influencers’ content or trends in online book communities to create their own videos. Not only are video concepts such as “booktubers pick my reads” or “should we believe the booktok/booktube hype?” incredibly derivative and circular when it comes to sourcing and producing book recommendations, the popularity of this genre of video as the sort of content that populates YouTube indicates the importance of booktube to booktube. Bookish social media communities are obsessed with the idea of themselves as a community, which then help formulate the different hierarchies and cliques and subgroups within it. This is also facilitated by the fact that booktube is a corner of YouTube that, in my experience, requires reciprocal community engagement.

With cari can read’s video “ranking your favorite author’s BEST and WORST book,” Cari takes viewer submissions of author names to offer her opinions on their writing, so she directly sources the content for the premise of this video from her audience. Cari contributes her opinion to the opinions from her audience in a way which necessitates discourse between creator and viewer. The parasocial aspect of booktubers and booktube viewers operates differently than in other online spaces, because the relationship between viewer and creator often creates the video content that the creator produces. This is also evident in the fact that many booktubers have popular online book clubs that hundreds if not thousands of people regularly participate in through livestreams and Discord servers.

I’ve also observed that somewhat uniquely, when compared to other types of communities on YouTube like with beauty gurus and fashion and lifestyle influencers, booktubers, myself included, regularly respond to comments they receive on their videos. Part of engaging with videos as a booktube viewer and creator is the ability to chat back and forth with like-minded people about books and recommendations. In answering the question of how and why she started her booktube channel, Rincey from RinceyReads said in a Q&A video in March of 2020, “Being home from college, I really missed talking to people about things like books… I just desperately was seeking other people to talk about books like this with.” The world of booktube provides space and community digitally to people who otherwise would not be able to participate in conversations and discussions about books outside of a classroom or maybe a real-life book club setting. That desire to find literarily-like-minded individuals online fosters a social media environment that sometimes feels less market-driven than other forms of social media content. Most booktubers know that they’re not going to gain 100,000 subscribers within a year from making videos talking about books; that’s not necessarily our goal when getting into it.

The competition for viewers and an audience on booktube often feels less crushing than other forms of internet content as well, specifically because of the diversity of people’s reading interests: your pre-existing taste in books and favorite genres deeply influences the types of booktubers you watch. A booktuber who primarily reads and recommends science fiction won’t draw in the audience of romance readers, and vice versa. These “types” of readers as represented by different booktubers, who are more or less ‘professional readers,’ creates a process of identifying oneself not just in books and book genres, but also the sort of person who would or does read certain books. These “types” of readers come with their own aesthetics, because social media’s imagery-focused nature and the talking-head style of video on YouTube portrays book covers alongside the visage of the people talking about them.

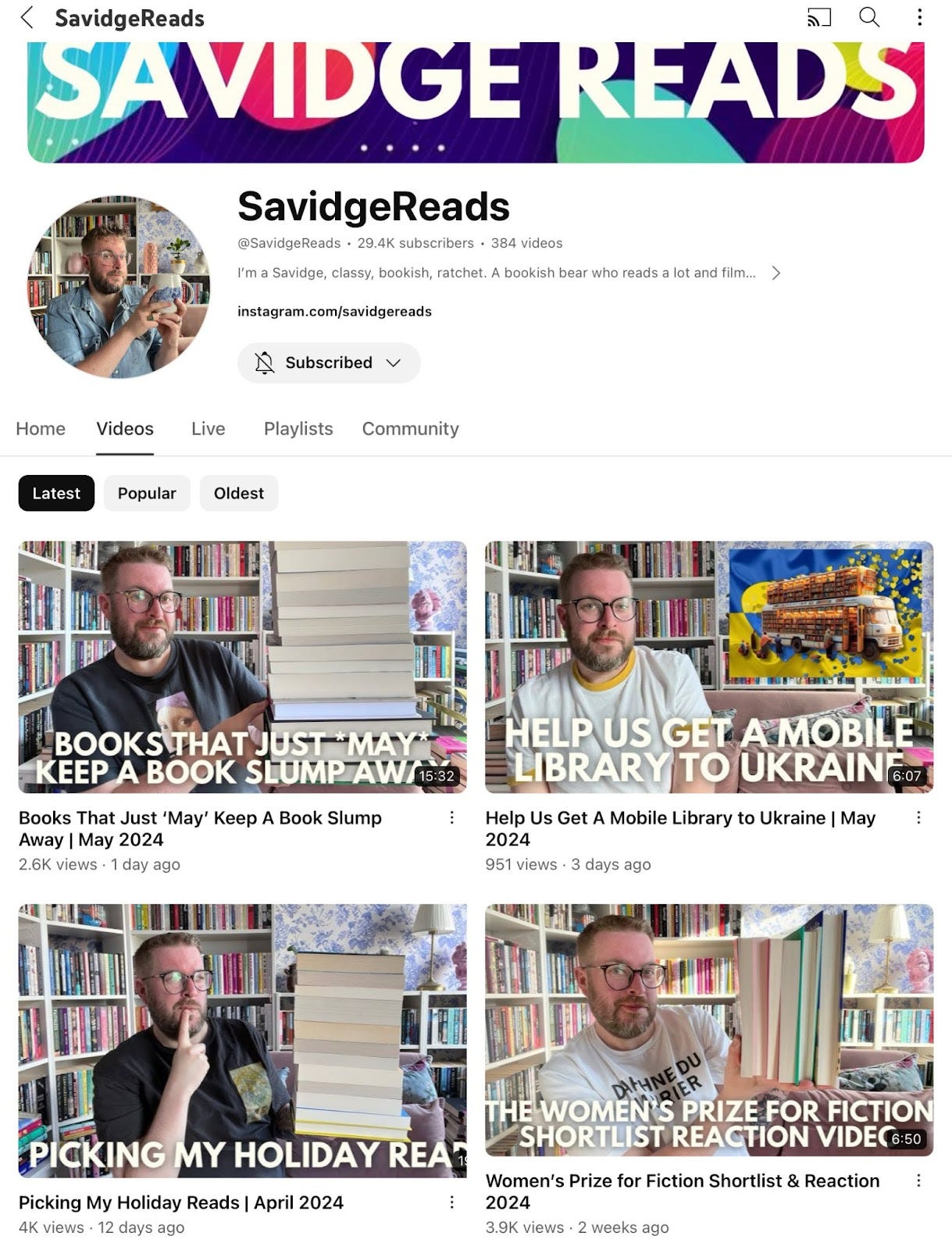

If you find the booktubers who primarily read, review, and recommend literary fiction and watch their videos consistently, you’ll notice that they and their videos are often quite aesthetically distinct from more genre fiction centric booktubers. Comparing the YouTube profiles of Chandler Ainsley, a romance-focused booktuber, and Simon of SavidgeReads, a booktuber who primarily reads and reviews literary fiction and nonfiction, there’s a clear difference between the target audiences they are reaching and what they’re reading from the video titles and thumbnails alone.

While Chandler’s thumbnails are colorful and highly edited, Simon’s are simple and straightforward. It’s unclear what specific books Simon is talking about in his videos from the thumbnails, which seems to indicate that regular viewers constitute most of his audience. Their familiarity with his taste through watching his previous videos creates a platform that seems to be less obviously demanding new viewer attention. Whereas with Chandler, her thumbnails heavily feature the covers of the books she discusses to draw in an audience, and the titles of her videos are working for clicks and views. Instead of titling the videos “march wrap up” and “april wrap up” on their own, the titles also include “WORST” and “FINALLY” in them seem to offer the audience a definitive opinion or hot take on books that Chandler can provide. She is grabbing the mic with the intention to be heard!

Chandler is just one of many romance-focused booktubers, and Simon is just one of many literary-fiction-focused booktubers. But genre is crucial to the landscape of booktube and what type of booktuber viewers watch. There are the genre-related categorizations of books that online book spaces help foster, ones that go beyond the conventions determined by the publishing market, up until the point that the publishing industry becomes attuned to its popularity and starts incorporating those online categorizations into marketing. “#SpicyTok” on the Barnes and Noble display is one example of this.

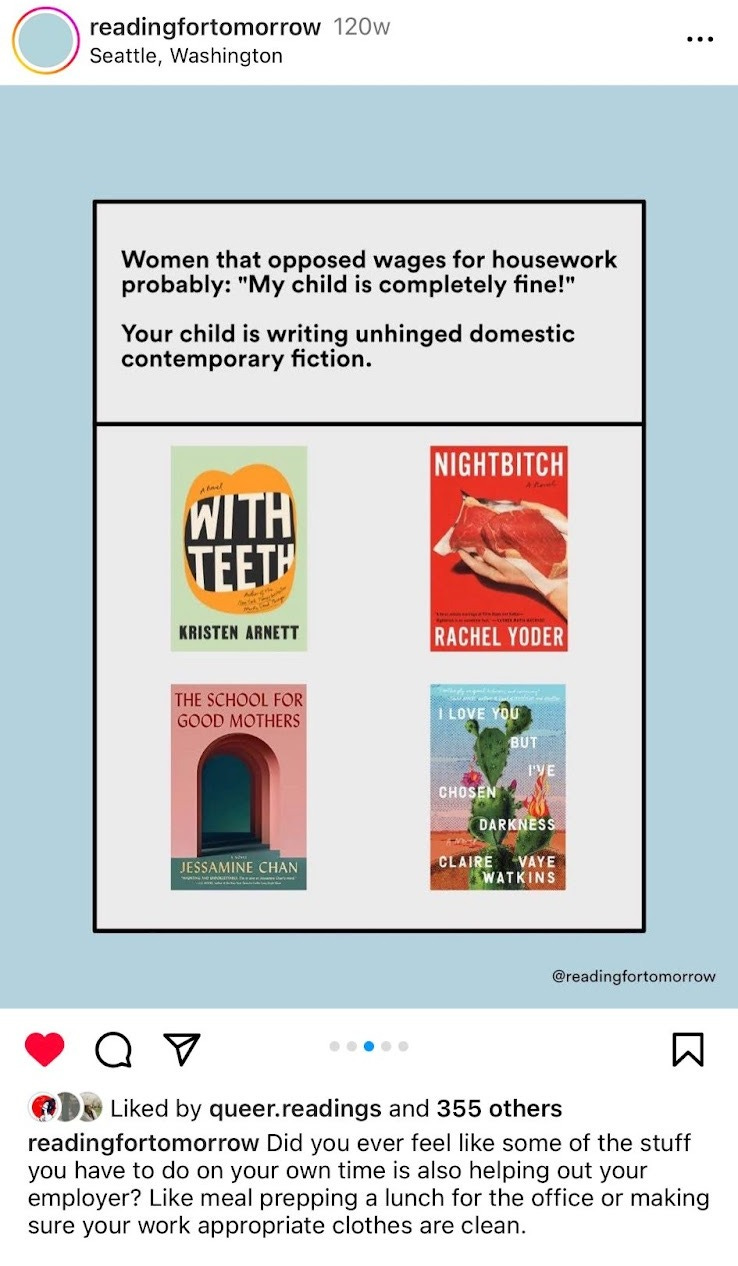

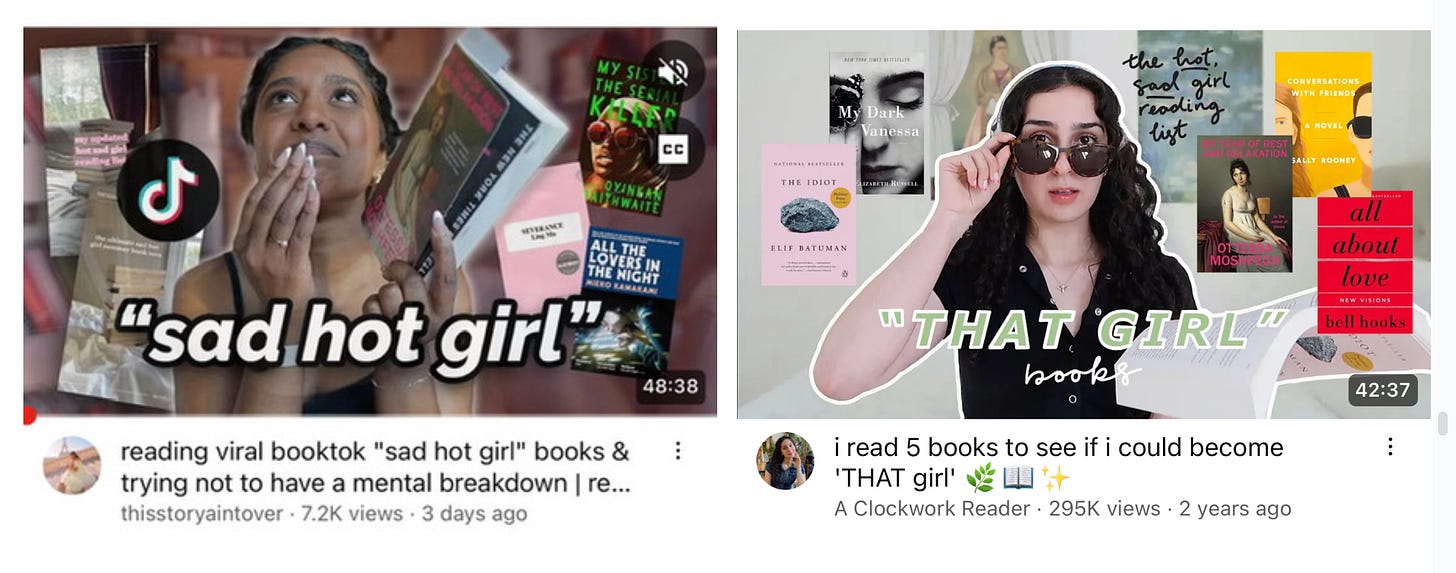

With the rising popularity of “weird girl fiction” or “sad girl books,” often literary fiction novels written by women, this type of book has basically become a subgenre of book unto itself, produced and reproduced through the bookish internet. Whether it be contemporary novels like My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh, The Idiot by Elif Batuman, Severance by Ling Ma, or books by Sylvia Plath and bell hooks, “the hot, sad girl reading list” that Hannah of A Clockwork Reader refers to in her reading vlog’s thumbnail speaks to the prevailing imagery of a genre that is supposedly by and for mentally ill, intelligent, beautiful women. Here, the aesthetic that the book seems to invoke defines the reader and the content of the video concept itself. Hannah’s video title, “i read 5 books to see if i could become ‘THAT girl’” articulates through a popular video that reading can potentially be used as a process of self-configuration. The books you read and how they affect, shape, and define you seem to be at the heart of the type of content that this subgenre of book fits into. Jananie of thisstoryaintover’s video title includes “trying not to have a mental breakdown” as related to her reading this genre of book. This internet-constructed subgenre of books is entrenched within the relationship between reader and text as much as it is about the writing itself. This subgenre was born of social media discourse of mostly young women categorizing books that they personally identify with as existing within its own corner of the literary world, especially within the landscape of the bookish internet.

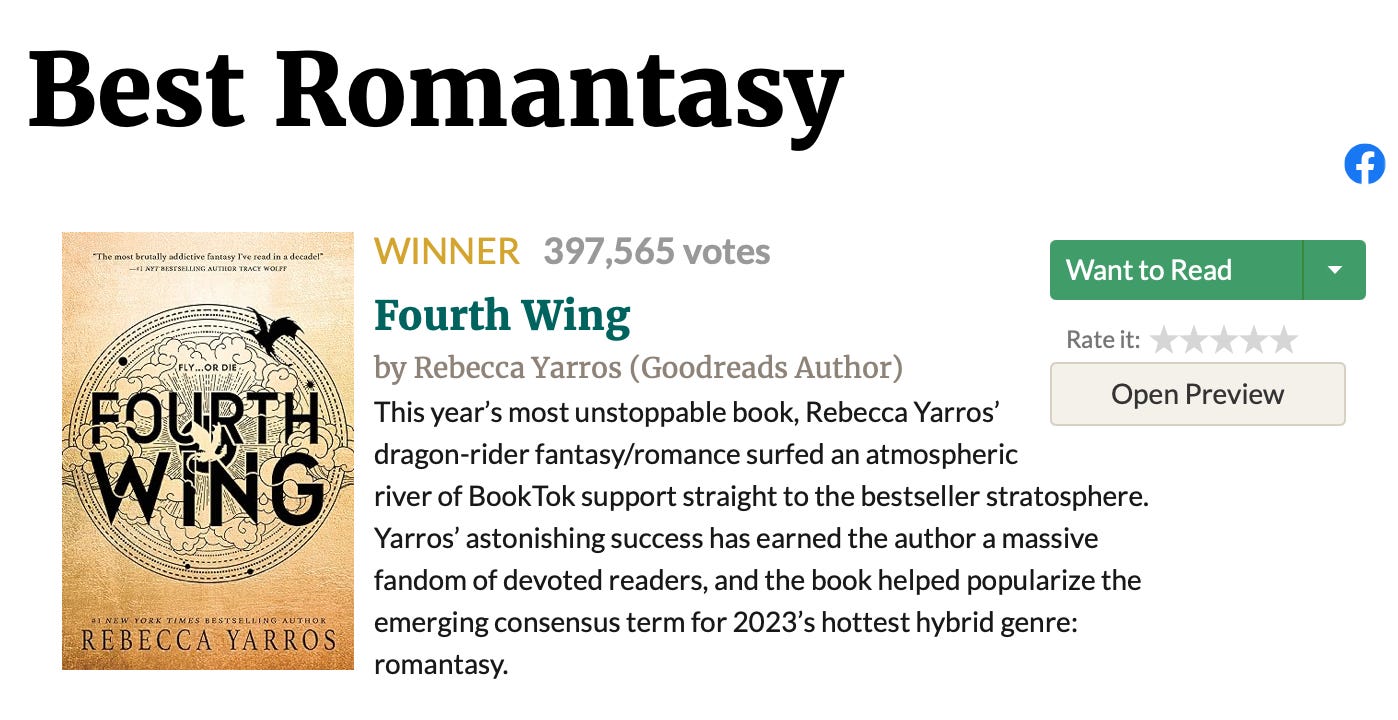

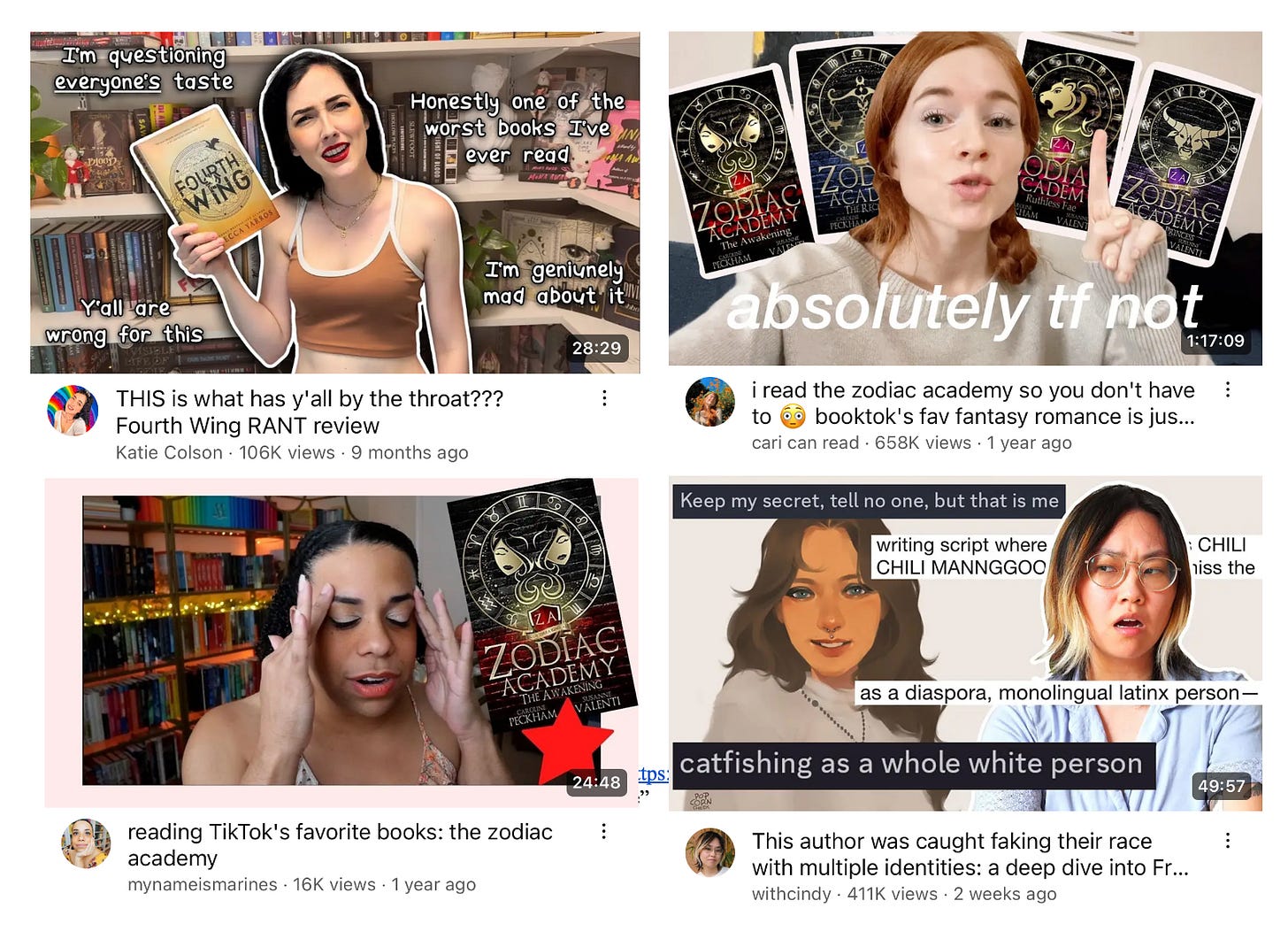

Another internet-created subgenre, “romantasy,” combines the pre-existing genre fiction categories of romance and fantasy. The popularity of this subgenre of book is evident in the fact that Goodreads created a new “romantasy” genre category for in its 2023 Goodreads Choice Award. Alongside the longstanding categories of Historical Fiction and Debut Novel, romantasy books were voted upon by Goodreads users at the end of 2023. The winner of that award category, Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros, has been the subject of many booktube videos, most of them being—in my estimation—very critical of its success and popularity. The importance of social media discourse and popularity in the contemporary world of books and publishing is evident in the Goodreads description of Fourth Wing alone: a “dragon-rider fantasy/romance” that rode the wave of “BookTok support straight to the bestseller stratosphere.” As popular as this novel is, it still belongs in what is understood to be a trashy genre, unlike the hot sad girl books that still land on college syllabi in a serious way.

Romantasy novels all seem to have a particular and unserious aesthetic to them even when regarding their cover design. Looking at the Goodreads Choice Awards nominations alongside Yarros’ Fourth Wing, the marketing of romance novels set in fantasy worlds within this particular category of genre fiction can be traced to online book spaces that named (and thus) created this genre. Subsequently or alongside Fourth Wing’s meteoric rise to popularity, what feel like copy-paste variations of that book have proliferated with the intention to achieve a similar level of virality. It sort of worked, because the same people who made videos critically reviewing Fourth Wing created similar videos about the runner up winner Zodiac Academy; Marines of mynameismarines reviewed both Zodiac Academy and Fourth Wing on YouTube.

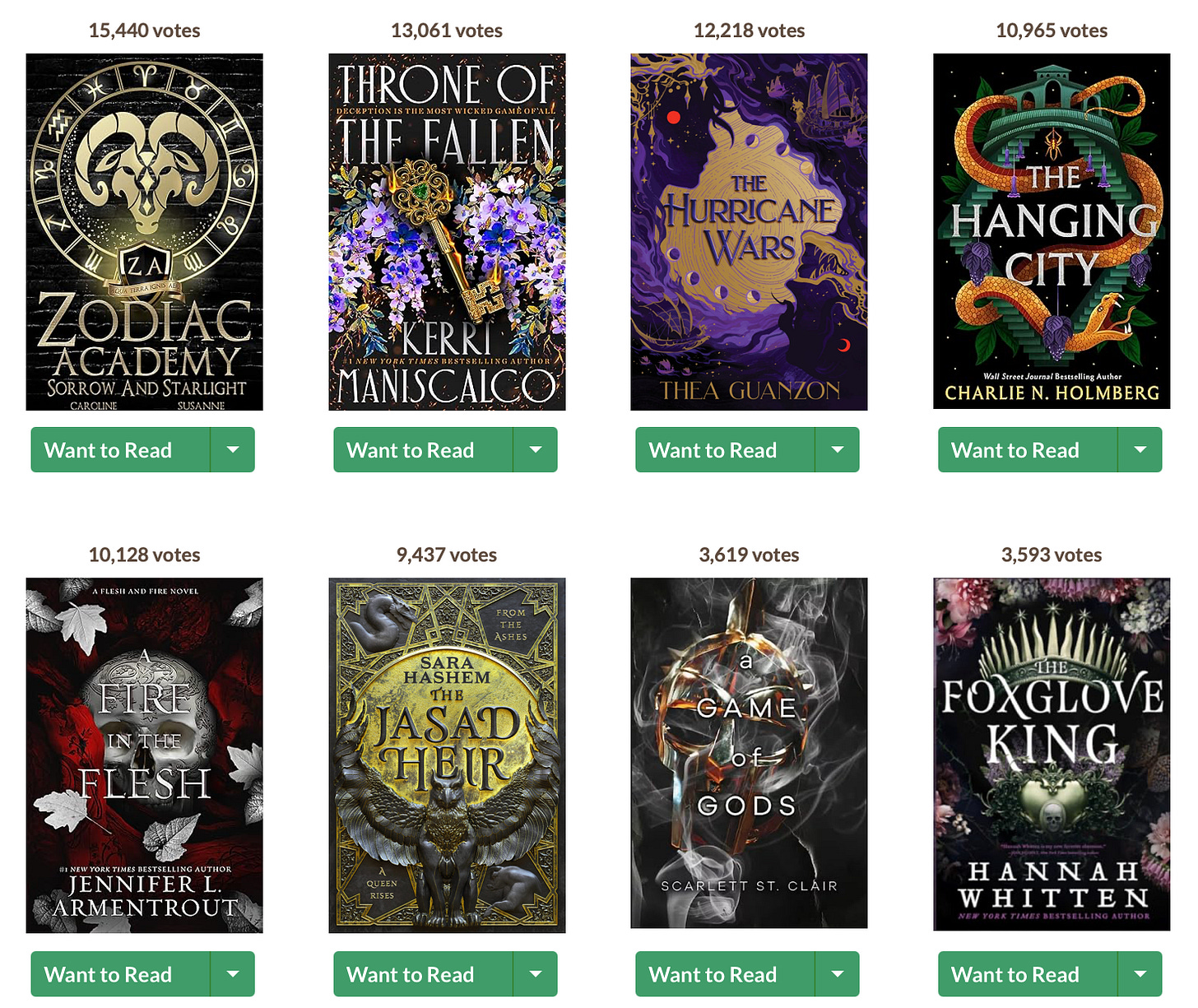

Interestingly, romantasy books, similar to smutty romance novels, often get trashed and critiqued online, while still being massively popular among consumers. Booktubers, among people who make YouTube videos online criticizing and commenting on media, often create videos about trashy novels in what I would argue is rage bait content, or at the very least, low-hanging fruit. Partly, these book takedown videos help narrow down what can be considered “good taste” in books online, and typifies books as worth reading or not worth reading. These book takedown videos are very often related to the drama in the discourse amidst online book spaces and how authors act on the internet. Or, the criticism of the text is couched within the context of the type of content that already exists about that book.

There is an entire genre of booktube video that is just “I read ____ so you don’t have to,” which is related to the genre of booktube video that delineates an author’s behavior in relation to their career as a writer. Both function as recaps of some sort of messy situation, whether that be the plot and bad writing of a book or the history of problematic behavior of authors. The best videos of this sort, in my opinion, combine both concepts into one video.

When Marines asks if a recently released young adult fantasy— romantasy?— novel is “a colonizer romance” in a book review video, it emerges from existing discourse on the bookish internet describing the book as such. In her video, Marines describes how the author was using booktok to promote this book before its release, creating expectations for the novel and building hype around it. Marines articulates her issues with the book’s writing, from the vague worldbuilding and time jumps to the juvenile and simplistic writing style on a sentence level. The crux of the discourse and the reason for her review emerges from the critique that this novel uncritically romanticizes the relationship between an imperialist successor to the throne and a girl from the colonized country who is his captor. Using textual evidence, Marines makes the point that this book not only is bad in that it is poorly written, it is also bad because the moral undergirding of the fictional world and relationships reflects violent political ideologies.

When articulating the racism, misogyny, or any other systemic issue as evidenced in contemporarily published fiction or behavior of authors, booktubers like Marines, or Cindy from withcindy, or Leo from The Book Leo, or lexi from lexi aka newlynova, all take on the moral arbitration of taste. None of them explicitly call the enjoyers of the books they tear apart in their book roast “rant review” videos bad people or stupid readers for liking these books. In fact, they often include disclaimers at the beginning of their videos explicitly telling viewers that if they did enjoy the book they are about to roast, they need not take personal offense, because these are merely their opinions. But they bring crucial and critical perspectives to a marketplace of publishing that is deeply shaped by what books sell and which authors get book deals, while also contributing to the cultural discourse surrounding what constitutes meaningful and intelligent reading. Simultaneously and more cynically, the way booktubers exist at the threshold of the formal publishing mechanisms of book marketing and the avatar of a reader as a consumer allows us to keep shitty books relevant through our bad-faith engagement.

While booktubers make content off of “hate reading” books, which is in my experience more likely to go viral than nearly any other genre of booktube video, they use the legitimacy of their opinions as affirmed by their viewers to be able to reach wide audiences with their criticisms of books, authors, and the publishing industry. Whether the video is merely a complete and thorough summary that basically Sparknotes a popular trashy novel, or an argument about the moral failures and problematic nature of a book using quotes from the text and its author’s online behavior as evidence, booktubers affect the marketplace of publishing as well as the so-called marketplace of ideas through the negative recommendation: here’s the whole book so you don’t have any need to read it yourself. Here is my point-by-point deconstruction of this novel’s plot, characters, themes, and what I find fault with. Viewers can then feel smart watching their video tearing down a trashy genre fiction novel because someone else has already done the work of engaging with that text and reviewing it negatively.

As much as booktube, or rather, the online book world at large, shapes the contemporary publishing market, booktubers themselves often are engaging in ‘the marketplace of ideas’ through presenting their varying opinions on books. The question of “Is this author someone we should be supporting?” reveals less so the supposed moral urgency around book choice, but rather how those tuned in to the discourse and online exposés of writers and books are entertained by drama. Even though we on the bookish internet exist outside the halls of consecrated literary institutions, it’s still a world where people want to tear down mass market books.

Social media book influencers present arguments not necessarily rooted in the professorial literary agenda of taste. Instead, we engage in the categorization of books within the scope and construction of the online bookish ecosystem we create. Collectively and individually, our influence on what is worth reading and why, whether popular books are “actually good” or not, and the best books in the contemporary publishing world is completely determined by our audience. It is no less of a market than anything else—the attention economy of internet views and engagement shapes our reading, recommendations, and reviews as much as the market of publishing determines what books get published and how they are promoted.